Humira (adalimumab)

Update: 21 February 2023

AbbVie overcharged the Dutch health care system as much as €1.2 billion for Humira. Now we are taking them to court.

Adalimumab (Humira): Introduction

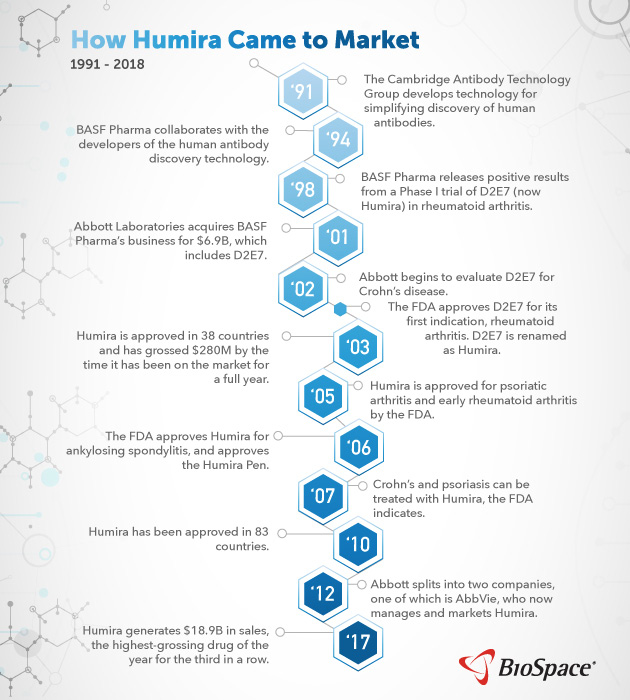

Adalimumab (brand name: Humira) is a prescription drug for rheumatoid arthritis that was first brought to the market in 2003 by the company Abbott (now, AbbVie). Abbott acquired adalimumab when it bought the German company Knoll from BASF in 2001 for $6.9 billion. Humira became the largest selling pharmaceutical product worldwide from 2012 until 2020. Between 2003 and 2020 AbbVie’s Humira netted $170 billion in global sales.

What is Adalimumab?

Adalimumab is an early example of a biopharmaceutical, a pharmaceutical drug based on a biological source. It was the first human monoclonal antibody, branded Humira: HUman Monoclonal antibody In Rheumatoid Arthritis. Specifically, adalimumab is derived from white blood cells; it acts to temper an overactive immune system. It was first tested as a treatment against sepsis, but this was abandoned. Adalimumab was then developed for rheumatoid arthritis but also works for many other indications, earning it the label ‘the Swiss army knife of drugs’. It needs to be injected subcutaneously every two weeks by patients.

Pricing and Cost

Costs and turnover from Humira in the Netherlands

Globally, AbbVie had an estimated turnover on Humira of about USD 170 billion between 2003-2020. In the Netherlands, turnover for 2004-2020 was calculated at €2.37 billion. AbbVie priced Humira in the Netherlands at about €460 per injection, resulting in an annual cost of around €12000 per patient. After EU market introduction in 2003, AbbVie registered Humira with EMA for 8 additional indications, such as psoriasis and inflammatory bowel diseases. This increased the number of patients that could be treated: for instance in the Netherlands the number rose from 5100 in 2006, to 15728 in 2011 and 21774 in 2018 (figure 1).  While user numbers increased enormously with added indications, these economies of scale did not translate into savings for the Dutch health system: the treatment costs remained rather constant at between €10,400 and €12,600 per year between 2006 and 2018. This significantly increased Humira’s total earnings per year, which rose from €63 million to €217 million in the Netherlands, with a peak of €223 million in 2014 (based on analysis of SFK, NZa’s Monitor reports and GIPdatabank). In 2012, the Dutch healthcare system made a change in order to lower healthcare costs: expensive medicines like Humira were no longer distributed through public pharmacies and financed through healthcare insurance of the individual users, but transferred to hospital care. This meant high-cost medicines could only be distributed by hospital pharmacies and thus integrated in the more centrally managed hospital budgets. The idea of this transition was that by making hospitals responsible for buying these expensive medicines, they would be better at negotiating lower prices for the medicines.

While user numbers increased enormously with added indications, these economies of scale did not translate into savings for the Dutch health system: the treatment costs remained rather constant at between €10,400 and €12,600 per year between 2006 and 2018. This significantly increased Humira’s total earnings per year, which rose from €63 million to €217 million in the Netherlands, with a peak of €223 million in 2014 (based on analysis of SFK, NZa’s Monitor reports and GIPdatabank). In 2012, the Dutch healthcare system made a change in order to lower healthcare costs: expensive medicines like Humira were no longer distributed through public pharmacies and financed through healthcare insurance of the individual users, but transferred to hospital care. This meant high-cost medicines could only be distributed by hospital pharmacies and thus integrated in the more centrally managed hospital budgets. The idea of this transition was that by making hospitals responsible for buying these expensive medicines, they would be better at negotiating lower prices for the medicines.

Key Facts (Netherlands)

- Humira was the most sold drug in the Netherlands 2009-2018 and worldwide 2012-2020.

- The number of Dutch patients on Humira increased more than 5x between 2006-2020, and yet the price remained the same until patent expiry in 2018

- In 2018, AbbVie dropped the price of Humira by 80% to fight off biosimilar competition

Humira enters the market

- 2001: AbbVie (as its legal predecessor Abbott Laboratories) buys Knoll Pharmaceuticals from BASF Pharma for US $6.9 billion.

- This purchase includes the monoclonal antibody, Adalimumab, then still designated D2E7.

- 2002: Humira is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, and over the next 7 years it is registered and marketed for 5 disease indications in the US.

- 2003: Humira is approved by EMA for the EU market. In the following years, 8 additional indications were registered by EMA.

- 2004: Humira is marketed in the Netherlands. Its main competitors are Remicade (infliximab, MSD) and Enbrel (etanercept, Pfizer).

- 2009: Humira surpasses Remicade and Etanercept and becomes the best-selling drug in the Netherlands.

Intellectual Property

Humira patents

When pharmaceutical companies market an innovative medicine such as Adalimumab, they use patents to control the use of their innovations. When a patent is in force, only the patent-owner is permitted to manufacture and sell the patented medicine (unless the patent owner grants permission via a patent licence). AbbVie tried several strategies to fight off biosimilar (competitive biologicals) entry in its profitable market: According to the non-profit research group I-MAK AbbVie has filed a ‘patent thicket’ of 247 additional patents on Humira in the U.S. in an attempt to extend its monopoly period. Although competitors could try to invalidate patents in court, this was a very long road. So the biosimilar companies made patent settlement agreements with AbbVie: in Europe, AbbVie would permit biosimilar competitors after 16 October 2018, in exchange for protection of the USA market until January 2023. AbbVie also changed the strength of its Humira from 50 to 100mg/ml, and removed citrate, which can sometimes cause painful injections. As biosimilar companies have to build their regulatory dossier on equivalency with the original Humira registration,this caused an extra barrier for market share. They launched the ‘old’ 50mg/ml biosimilars in 2018. Only in 2021 the first 100mg/ml biosimilar reached the NL market.

Humira patents expiry

After the expiry of patent protection in Europe on 16 October 2018, many hospitals in the Netherlands launched new tenders to benefit from lower adalimumab prices. Five ‘biosimilars’ products competed with Humira. AbbVie immediately dropped the price of Humira by around 80%. Biosimilars achieved a 50% volume share, which translated to a 40% market share. AbbVie kept 60%. The average annual price per patient dropped from €9,967 in 2018 to €2,284 in 2020. See figure 1 above. Whereas Europe benefited from reduced prices due to biosimilar entry, the USA saw AbbVie increasing Humira prices, in order to make up for the ‘losses’ in Europe. In the USA AbbVie followed a different pricing strategy by continuously increasing the price (actually in tandem with Pfizer’s Enbrel). This led to a USA Congress hearing where AbbVie had to testify in May 2021. The Congress report was published 8 December 2021.

Humira: A Case of Interest for PAF

At the Pharmaceutical Accountability Foundation (PAF), we believe that pharmaceutical companies should be called to account when they make excessive profits based on excessive pricing of their medicines, as these excessive profits are paid by our healthcare system, which could have also used them to pay other healthcare costs.

Humira has been the best-selling drug worldwide from 2012 until 2020. Between 2004-2018 it was sold in the Netherlands for a high price. AbbVie netted €2.37 billion in the Netherlands alone during this period. When biosimilars entered the market in 2018, the price dropped by 80%.

The 80% price drop after patent expiry indicates that Humira was sold at a very high price. AbbVie kept the Humira price high until 2018 thanks to its monopoly position in the Dutch market. Pharmaceutical companies are expected and allowed to make reasonable (fair) profits. They are also expected to invest in new R&D and develop new medicines. They of course can deduct reasonable costs for production and sales of their product. But these excessive prices imposed undue costs on the Dutch healthcare system, resulting in a displacement of care.

Biosimilars are important in the medicines market because they increase competition and drive down prices. AbbVie’s aggressive post-2018 campaign to retain its dominant position on the European market may deter future biosimilar innovation, and contribute to the price of drugs remaining high.

Displacement of care

To learn more about displacement of care and why it matters for public health, please see our article on the issue.

How is the Pharmaceutical Accountability Foundation acting on this case of interest?

On the 21st of December 2021, the Pharmaceutical Accountability Foundation (PAF) sent a Letter of Liability to AbbVie. In accordance with the value that PAF attaches to fair pricing, we have called AbbVie to account for the excessive pricing it charged for Humira between 2004-2018 while the drug was still protected by patent. We have asked AbbVie to respond to our view that it acted unfairly by charging these excessive prices, and that this resulted in a displacement of care within the Dutch healthcare system, creating access barriers to healthcare products and services for Dutch citizens, and resulting in a severe loss of Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs).

The Foundation is of the opinion that AbbVie acted contrary to fundamental human rights, including the right to life and the highest attainable standard of health, which includes the right to access essential medicines. Pursuant to the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the Human Rights Guidelines for Pharmaceutical Companies in relation to Access to Medicines, and the OECD Guidelines, there is a corporate responsibility to respect human rights, which AbbVie has breached by charging excessive prices for its drug Humira.

Finally, Abbvie has in our view also breached competition rules under Dutch and European law, by abusing its dominant market position through excessive pricing of Humira, and by discouraging biosimilar and generic competition, thereby further limiting access to essential health services for Dutch and European citizens.

The Foundation has requested a meeting with AbbVie in an effort to settle this matter out of court, and has asked the company to respond substantially by 28 February, 2022.

Legal Principles applicable to the Humira case

The right to life

Article 2.1 ECHR: “1. Everyone’s right to life shall be protected by law. No one shall be deprived of his life intentionally save in the execution of a sentence of a court following his conviction of a crime for which this penalty is provided by law.” Article 6.1 ICCPR: ‘Every human being has the inherent right to life. This right shall be protected by law. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his life.’

The right to the highest attainable standard of health

In Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), States Parties recognise ‘the right of everyone to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health’. The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), which supervises the implementation of the ICESCR, has published a comprehensive interpretation of the aspects necessary for the right to health’s realisation in its General Comment 14 (GC 14). Below is a summary of GC 14’s key elements:

(1) States have duties to respect, protect, and fulfil the right to health;

(2) It is recognised that the right to health is subject to resource constraints and progressive realisation;

(3) Nonetheless, certain aspects of the right to health are of immediate effect;

(4) Access to healthcare goods, services and facilities should be available, accessible, acceptable and of good quality:

(5) The ‘accessibility’ qualifier includes the dimension of ‘affordability’;

The right to health imposes legal obligations on governments to realise this right to the greatest extent possible. Access to medicines is a fundamental element of this right. Governments therefore also have the duty to create laws and policies that promote and ensure citizens’ access to medicines.

The Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights

The United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights hold that ‘the responsibility to respect human rights is a global standard of expected conduct for all business enterprises wherever they operate.’ This standard ‘exists independently of States’ abilities and/or willingness to fulfil their own human rights obligations’. Private companies therefore have stand-alone obligations to respect human rights. Beyond the general standards outlined in the UN Guiding Principles, The Human Rights Guidelines for Pharmaceutical Companies in relation to Access to Medicines indicate that pharmaceutical companies have specific obligations in relation to access to medicines, and provide standards for determining if, and when, pharmaceutical companies may have violated human rights and should be held accountable. Principle 33 reads as follows: ‘When formulating and implementing its access to medicines policy, the company should consider all the arrangements at its disposal with a view to ensuring that its medicines are affordable to as many people as possible.’

The unwritten duty of care

According to section 162 of book 6 of the Dutch Civil Code (DCC), ‘a person who commits a tort towards another which can be imputed to him, must repair the damage which the other person suffers as a consequence thereof.’ The third category of torts relates to acts or omissions that violate ‘a rule of unwritten law pertaining to proper social conduct’. This last category constitutes an unwritten standard of due care, any breach of which will be considered a tort. The Court determines this standard of care by considering ‘all relevant facts and circumstances of the case’. In the landmark judgement against Royal Dutch Shell, the Dutch Court paid significant attention to the UN Guiding Principles. This case sets an important precedent, with the Court ruling that private companies have individual obligations (in this case, to reduce CO2 emissions), independently of existing State obligations, and that this obligation is enshrined in Dutch tort law in article 6:162. Accordingly, pharmaceutical companies also have a corresponding duty of care, which may be breached by, e.g., setting high prices that result in displacement of care and loss of life.

The OECD Guidelines

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is a forum composed of governments which promotes trade and free market policies. The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (OECD Guidelines) are a set of recommendations aimed at encouraging responsible business conduct. The Guidelines set international standards relating to many areas of business conduct, including human rights. They are not legally binding on the companies themselves, but on the signatory governments. Corporate misconduct can be resolved through a special grievance mechanism, implemented through a representative in the signatory State (known as a National Contact Point/NCP). Most importantly, the OECD Guidelines establish that the responsibility to respect human rights applies to corporate entities, such as pharmaceutical companies.

Abuse of a dominant market position

Article 24.1 of the Dutch Competition Act (DCA) holds that ‘undertakings are prohibited from abusing a dominant position’. More specifically, Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), states: ‘Any abuse by one or more undertakings of a dominant position within the internal market or in a substantial part of it shall be prohibited as incompatible with the internal market in so far as it may affect trade between Member States. Such abuse may, in particular, consist in:

(a) directly or indirectly imposing unfair purchase or selling prices or other unfair trading conditions;

(b) limiting production, markets or technical development to the prejudice of consumers;

(c) applying dissimilar conditions to equivalent transactions with other trading parties, thereby placing them at a competitive disadvantage;

(d) making the conclusion of contracts subject to acceptance by the other parties of supplementary obligations which, by their nature or according to commercial usage, have no connection with the subject of such contracts.

Market dominance usually occurs when a private company enjoys a position allowing it to function independently from its competitors, and controls a majority share of the market. This is sometimes measured by market share – e.g., above 40% – but this is not a perfect measure of dominance. In United Brands v Commission, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) described the dominant position as one ‘of economic strength enjoyed by an undertaking which enables it to prevent effective competition being maintained on the relevant market by affording it the power to behave to an appreciable extent independently of its competitors, customers and ultimately of its consumers’. Misusing the regulatory framework by, for example, extending patent protection for drugs in order to delay the market entry of generic products, is considered to be an anti-competitive practice and an abuse of such a dominant market position. Charging excessive prices for a medicine during the patent protection period can also be considered an abuse of dominance.